In previous posts, I’ve written about integrating the crosscutting concepts (CCCs) in curriculum. The CCCs are a set of thinking tools, or epistemic heuristics, for science. Each CCC can be imagined as a lens through which we examine phenomena. Each lens reveals a different aspect of the phenomenon that should be included in an explanation of how the phenomenon works. In this post, I present a way to coherently integrate the CCCs into a curriculum unit.

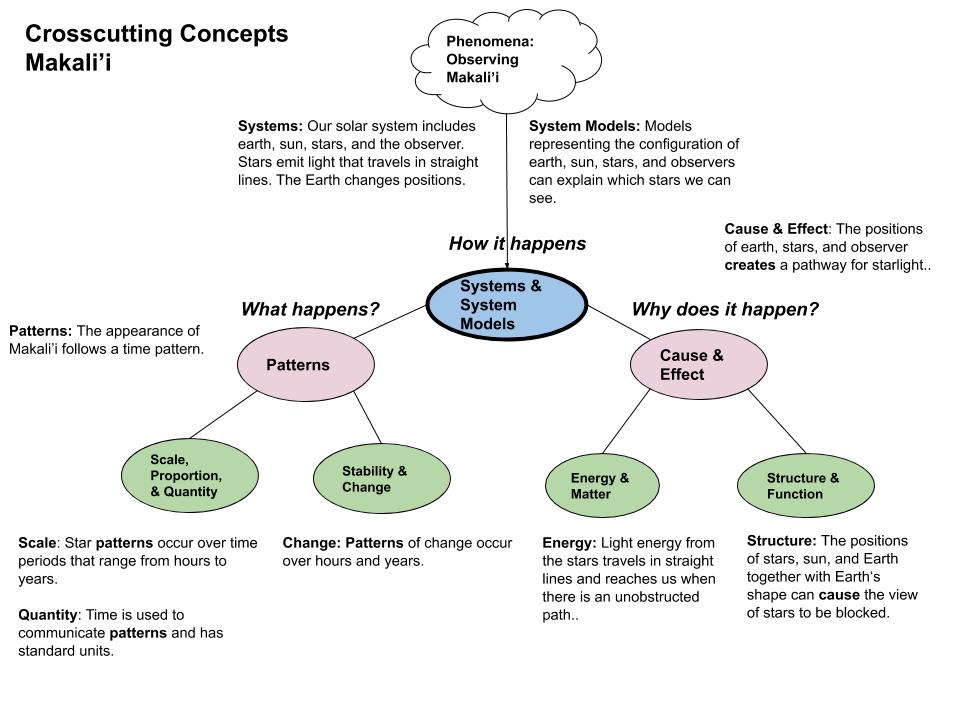

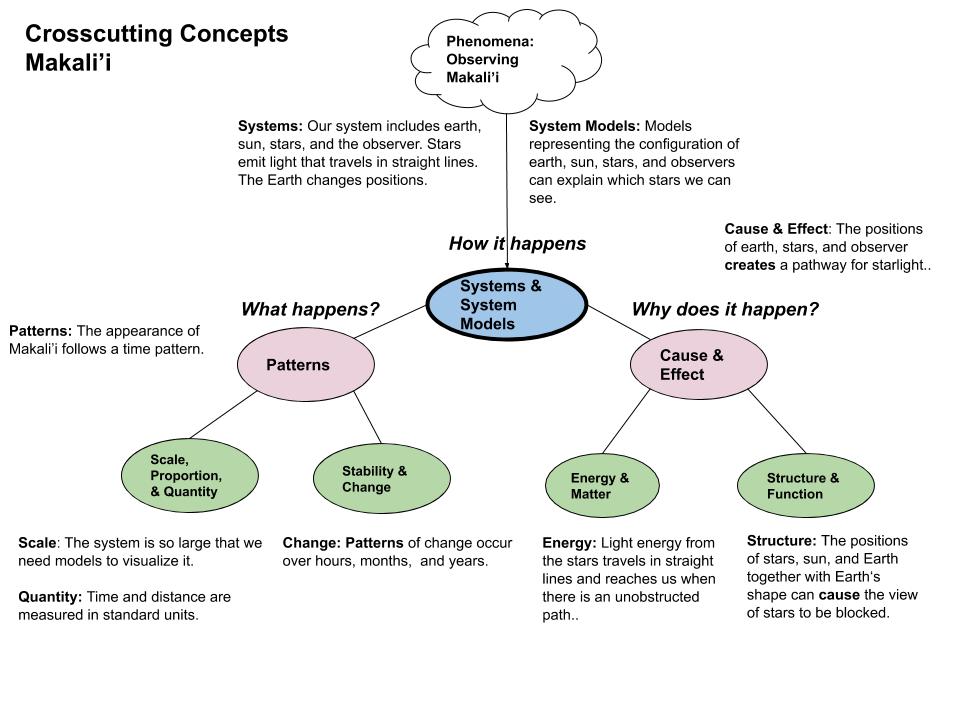

I’ve used my graphic organizer to identify how each CCC applies to the phenomenon. The figure below is for the phenomenon of Makali’i rising at sunset each November, which is an indication for the start of the Hawaiian new year. In this post I will illustrate how to weave the CCCs into instruction over the course of a unit. Each of the CCCs is introduced in the unit as their investigations reveal related aspects of the phenomenon.

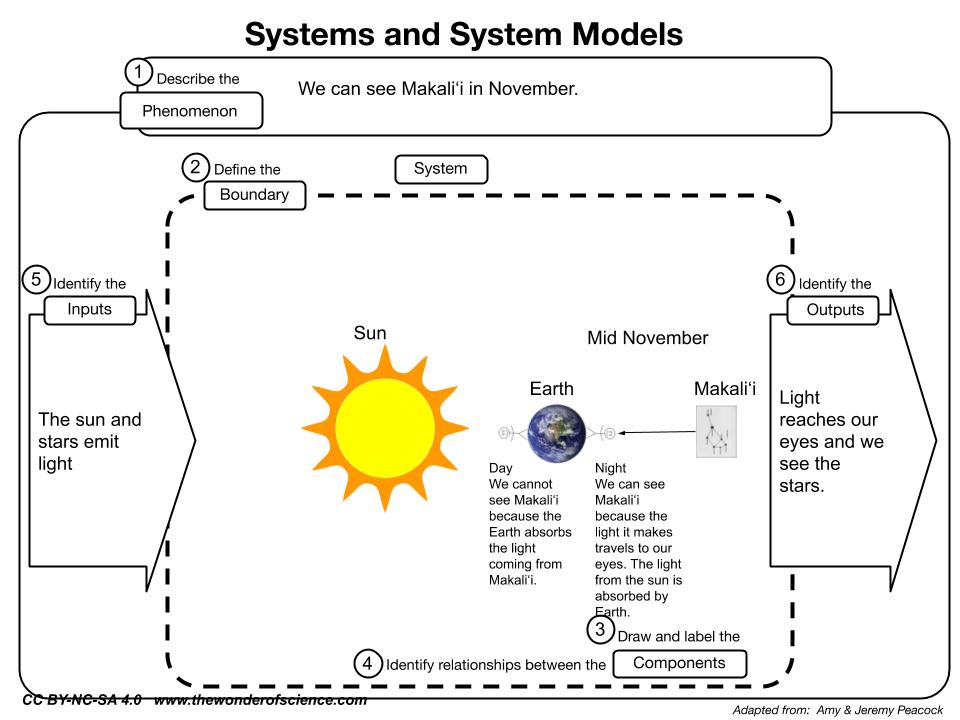

Systems and System Models is the Foundation

A key feature in the unit is student modeling. Systems and System Models is the foundational CCC (blue oval in the figure). At the beginning of the unit students create a system model that reflects their initial understandings. The model should include the important parts and how the parts interact. Students revisit the model two more times in the unit, at the middle and near the end. In the middle of the unit students refine the model using evidence from their investigations. Near the end of the unit students refine the model again to integrate their new understandings and explain the anchoring phenomenon. These refined models should address more CCC elements.

Begin Modeling with the Basics – Patterns and Cause & Effect

At the beginning, modeling should focus on the two first-order CCCs – Patterns and Cause & Effect (pink ovals in the figure). Students identify patterns in the phenomenon and attempt to explain the cause of the patterns. They do not yet know the cause and effect relationships that explain the phenomenon. This is a good time to elicit students’ ideas and create a class list. Teachers can offer sentence starters for students to record their ideas about the cause and effect relationships. After individual think time and small group sharing, teachers can gather ideas from the whole class into a list that is a class resource for modeling.

Next, students work in small groups modeling the phenomenon. Teachers can ask questions that help students use the other CCCs and focus their thinking. Based on the ideas a student has, teachers can focus a student’s thinking on a specific part of the phenomenon using focusing questions.

Focus Student Thinking with Remaining CCCs

The teacher should have a list of questions written in advance that target each of the CCCs as they apply specifically to the anchoring phenomenon. Let’s look at examples for the phenomenon of the rising of Makali’i. STEM Teaching Tool #41 is helpful for creating good focusing questions.

Scale, Proportion, and Quantity

- Can an observer on Earth see the cause of the changes in the constellations that we see?

- Is the cause too large or does it take too long to see directly?

- How can a model make this cause easier to see?

Stability and Change

- What explains why we see different constellations over a year?

- What explains why the same constellation returns every year at the same time?

Energy & Matter

- How does energy (light) travel in this system?

- What causes an observer to see a constellation?

Structure & Function

- How do the spatial relationships among the parts of the system cause the observer to be able to see a constellation?

Teachers should select which questions to ask based on what ideas students are trying to express in their models. The purpose of questioning is to elicit what students already know and help them express their ideas in models. The questions should not be used to try to change students ideas at this point. The teacher needs to use their judgement to determine which questions will help student thinking and which questions are not productive at this point in the unit.

Revising Models After Investigations

At the middle and near the end of the unit, students revisit their models to improve them. The focusing questions listed above can be refined to ask students to address how new evidence might be included in their models. For example, in the Makali’i unit students learn how Earth’s rotation makes the sun and stars appear to move over the day and night. They learn how the same motion can look different from different frames of reference. A person sees the Earth as stationary and the stars moving, while a person in space sees the stars as stationary the Earth rotating. Teachers can revise the focusing questions to help students examine how this finding affects their models. Here are some examples for two CCCS.

Stability and Change

- How does the Earth’s rotation explain why our view of the sky from Earth changes?

- How does the Earth’s rotation explain why constellation rise and set each evening?

Structure & Function

- How does the Earth’s rotation affect our ability to see a constellation from Earth?

These revised focusing questions help student think about how to integrate their new knowledge into their models.

In this way, we can strategically integrate all the CCCs through iterative modeling and discourse tools. It may be that some CCCs are not helpful for certain phenomena. It may be better to introduce some CCCs later in the unit rather than at the beginning. Those decisions would be made on a case-by-case basis.

What do you think about these ideas? Let me know in the comments or on Twitter.

Revolutionizing Science Education with Vernier Connections powered by Penda

Vernier Connections, in collaboration with Penda Learning, revolutionizes science education by enabling students to actively engage in investigative learning. This program emphasizes real-world phenomena and employs Vernier sensors for data collection, fostering critical thinking and scientific practices. It aligns with NGSS standards while providing structured, student-centered experiences that enhance comprehension and inquiry.

Transforming a Physics Lessons about Wave Properties

Are you transforming your physics course to NGSS? I took an old lesson of mine about properties of waves and transformed in to a phenomenon-driven storyline. The original activity was an inquiry-based lesson on wave properties. You can find it on the PhET website. I wanted to update this lesson to align with the NGSS…

Developing a Particle Model of Matter

On September 15, we started Lesson 2-3 of The Garbage Unit. This lesson develops the idea that solids and liquids are made of particles and uses this idea to explain sugar dissolving in water. The day before this lesson, students made predictions about what happens to sugar when we dissolve it in water. Most students…